Why wearables cannot hide behind short support cycles anymore

A new EU regulation is about to change the way wearable tech companies think about updates. The Cyber Resilience Act (CRA) requires that smartwatches, fitness trackers and other connected devices meet strict cybersecurity obligations, including long-term product support. And this is more than just words on paper.

For wearables, it means something very specific. If you ship a device that connects to an app or cloud service, you are now responsible for keeping it secure for as long as someone is likely to wear it.

Why support windows just got more serious

Wearables have often lived in a quiet grey zone when it comes to updates. A fitness band might get a firmware patch or two, then drift into silence while it continues to sell in online stores. The industry has long relied on short-term support and fast model churn. But that is no longer a safe strategy in the EU.

The Cyber Resilience Act turns what used to be best effort into legal obligation. If a smartwatch is marketed as something you’ll wear daily for training, sleep, or health insights, then it must continue receiving security fixes for as long as that use remains reasonable. The law doesn’t specify an exact number of years. Instead, it forces companies to justify the support window they choose, based on the product’s function, marketing and price point.

Essential reading: Top fitness trackers and health gadgets

That flexibility isn’t a loophole. It’s the point. A tracker marketed as a lifestyle companion for fitness and wellbeing will be held to different expectations than a connected toy. What matters is that the company can explain how long the device will stay safe to use.

Cheap wearables are the first to feel the heat

The CRA’s biggest impact may fall on low-cost and white-label devices (produced by manufacturers who sell devices without branding or under flexible branding agreements). Many of these rely on off-the-shelf firmware stacks with little to no patching infrastructure behind them. Once sold, there’s often no clean way to fix bugs or roll out urgent updates.

That model is now at risk. A €25 wearable that ships with Bluetooth, app syncing and basic health tracking must now carry a long-term support burden. That includes having a working update mechanism and a vulnerability handling process. If a bug appears, it must be fixed. If a security issue is found, it must be disclosed and patched. That kind of maintenance costs money long after the sale.

For smaller brands, this may force hard decisions. Some will need to raise prices. Others will have to reduce the number of models in circulation or drop the EU market entirely. This will be especially painful for brands that depend on high turnover and minimal backend support.

The countdown has started

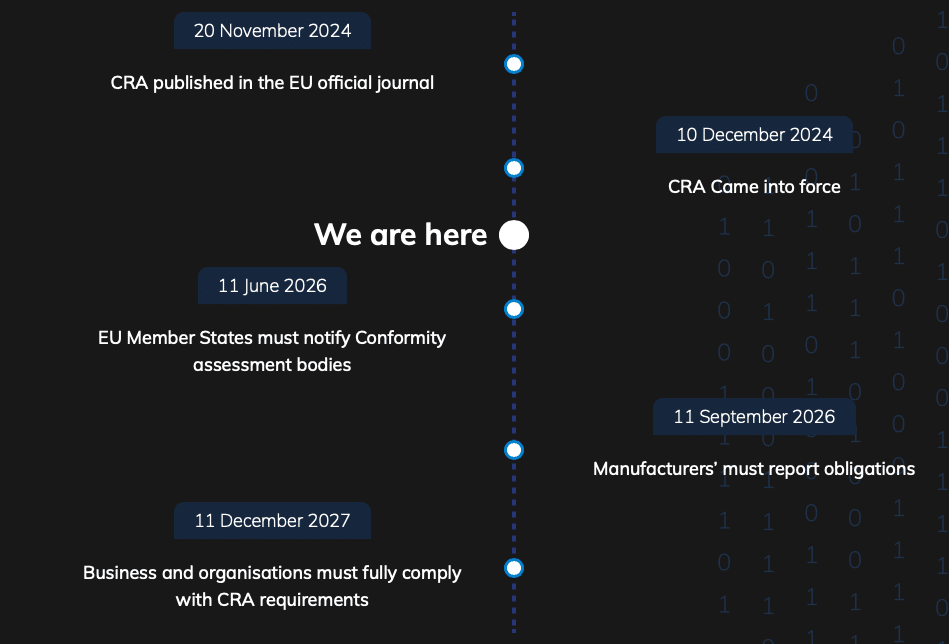

The CRA entered into force in early 2024. But manufacturers have until 11 December 2027 to fully comply. That means companies now have a clear runway, but it’s not a long one.

By that date, wearable tech sold in the EU must meet the security-by-design principles laid out in the regulation. That includes providing updates for a reasonable period, implementing secure development practices, and maintaining documentation that proves compliance. Products must also carry CE markings to show they meet CRA requirements.

After the deadline, non-compliant devices will not be allowed on the market. Selling them, even through third-party retailers, could trigger enforcement action.

Support infrastructure must work in reality, not just on paper

One of the subtler rules in the CRA is that patches must actually reach users. Having a fix on a server somewhere is not enough. The update process needs to be functional, reliable and usable.

This has implications for app support as well. If a wearable depends on a smartphone app to receive firmware updates, and that app is no longer maintained, the update pathway effectively breaks. That becomes a compliance issue, even if the device is technically still supported.

Manufacturers will need to think more carefully about app sunset timelines and Android/iOS compatibility. App stores change. APIs get deprecated. If your update mechanism depends on an ecosystem you don’t control, it must be monitored and maintained.

What changes from here

The CRA doesn’t stop anyone from building affordable wearables. It just stops them from being disposable in a way that puts users at risk. If a device is still worn, it must still be protected. That’s the baseline the law now enforces.

Brands like Apple, Garmin and Samsung already operate with long-term update infrastructure and mature firmware pipelines. They’re unlikely to need major changes. But for companies like Xiaomi and Realme and the many white-label fitness bands found across online marketplaces, the Act may force a rethink. Shared firmware stacks, short-lived chipsets and vague support timelines are no longer safe defaults.

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter! Check out our YouTube channel.

And of course, you can follow Gadgets & Wearables on Google News and add us as your preferred source to get our expert news, reviews, and opinion in your feeds.